- Language

- MENU

STORY 1

Clay, Craftsmanship, and Bunmei Kaika

For 250 years during the Edo period, Japan was closed to the outside world and essentially a self-contained culture. While arts and craftsmanship flourished during this period, Japan was still very much a pre-industrial society in 1850.

The opening of Japanese ports to American trade by Commodore Perry in 1854 triggered an influx of products and technologies, made possible by the industrial revolutions of the Western world. Under the slogan “Bunmei Kaika” (civilization and enlightenment), the new government formed by the Meiji Restoration in 1868 aggressively pursued modernization, aiming to become internationally recognized as a civilized nation.

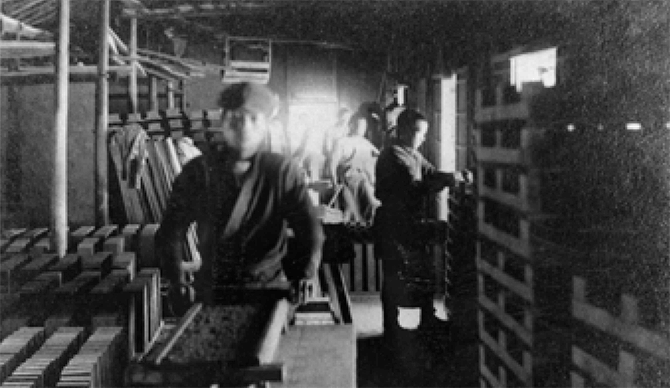

Learning from the West, rapid changes took place in Tokyo and other major cities. Urban infrastructures and Western-style stone and brick buildings were developed, often designed by foreign architects. Such modernization was supported by products made from clay, such as bricks, tiles, terracotta and earthenware pipes. Hatsunojo Ina, one of LIXIL's founding fathers, played a pivotal part in the development of the ceramic industry during this time, uniting craftsmanship with tools for mass production and, thereby, creating products that changed the lives of Japanese people.

STORY 1

Clay, Craftsmanship,

and Bunmei Kaika

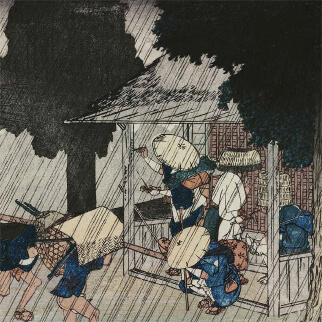

For 250 years during the Edo period, Japan was closed to the outside world and essentially a self-contained culture. While arts and craftsmanship flourished during this period, Japan was still very much a pre-industrial society in 1850.

The opening of Japanese ports to American trade by Commodore Perry in 1854 triggered an influx of products and technologies, made possible by the industrial revolutions of the Western world. Under the slogan “Bunmei Kaika” (civilization and enlightenment), the new government formed by the Meiji Restoration in 1868 aggressively pursued modernization, aiming to become internationally recognized as a civilized nation.

Learning from the West, rapid changes took place in Tokyo and other major cities. Urban infrastructures and Western-style stone and brick buildings were developed, often designed by foreign architects. Such modernization was supported by products made from clay, such as bricks, tiles, terracotta and earthenware pipes. Hatsunojo Ina, one of LIXIL's founding fathers, played a pivotal part in the development of the ceramic industry during this time, uniting craftsmanship with tools for mass production and, thereby, creating products that changed the lives of Japanese people.

Wright's Imperial Hotel

The Imperial Hotel was initially built in 1890 to provide comfortable accommodation to guests from abroad. As Japan modernized, the number of foreign visitors grew rapidly in the early 1900s. To increase capacity, the hotel commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the second building in 1916.

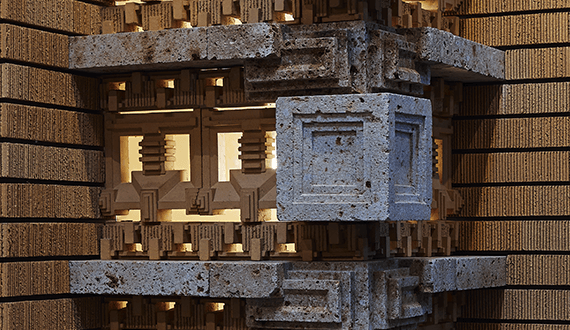

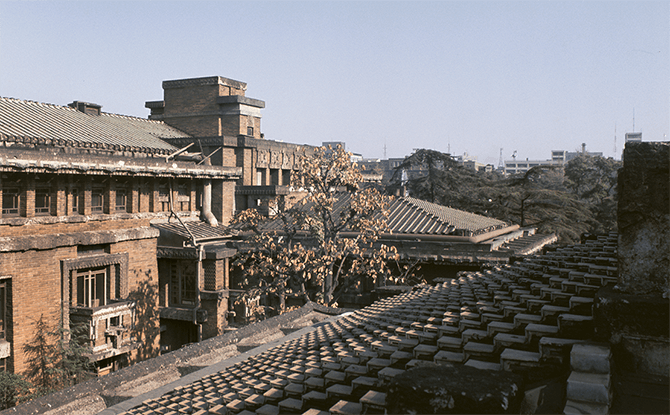

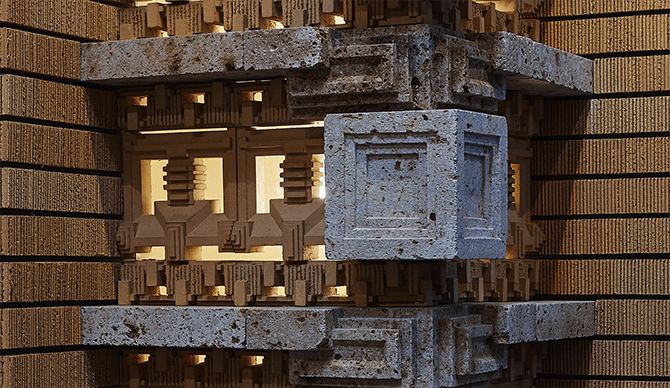

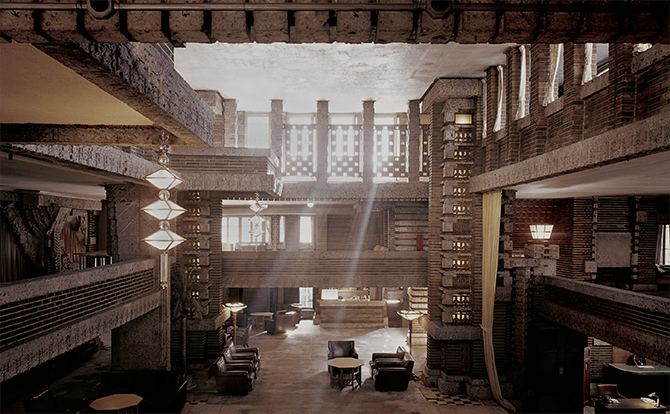

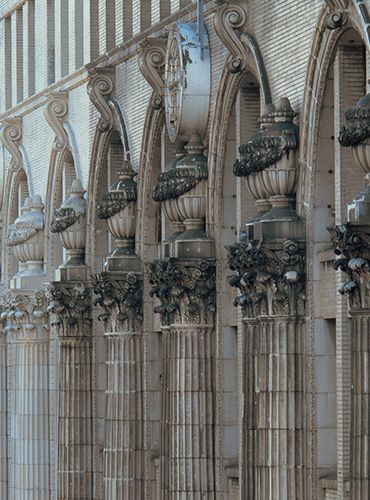

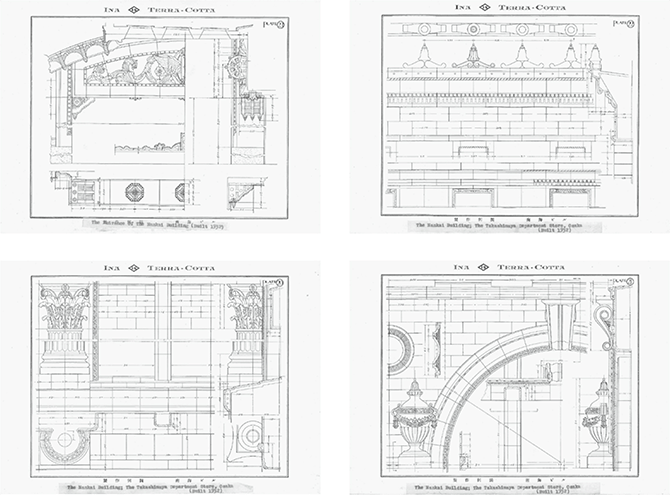

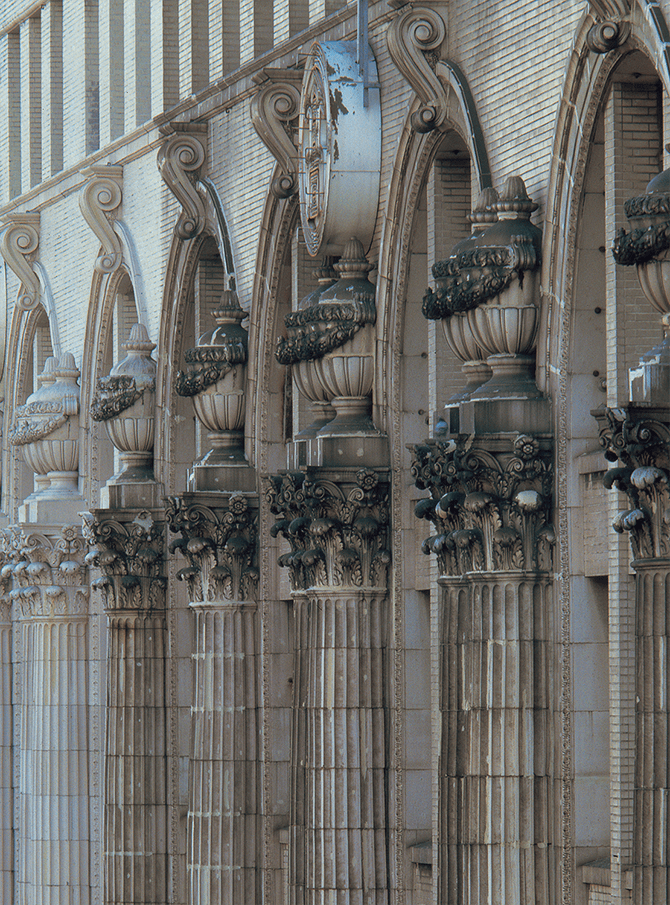

Wright used a revolutionary architectural design that signified Japan's modernity and the cultural interaction between the East and the West. Unlike other typical Western-style red-brick buildings of the time, Wright used yellow scratch face bricks, ornamental terracotta and carved Oya lava stones, resulting in warm earth tones that matched Japanese sensibilities.

The Imperial Hotel became one of the symbolic architectures of modern Japan. Copying the style, scratch face tiles became a popular exterior material, starting the industrial development of exterior building materials suitable for buildings in Japan.

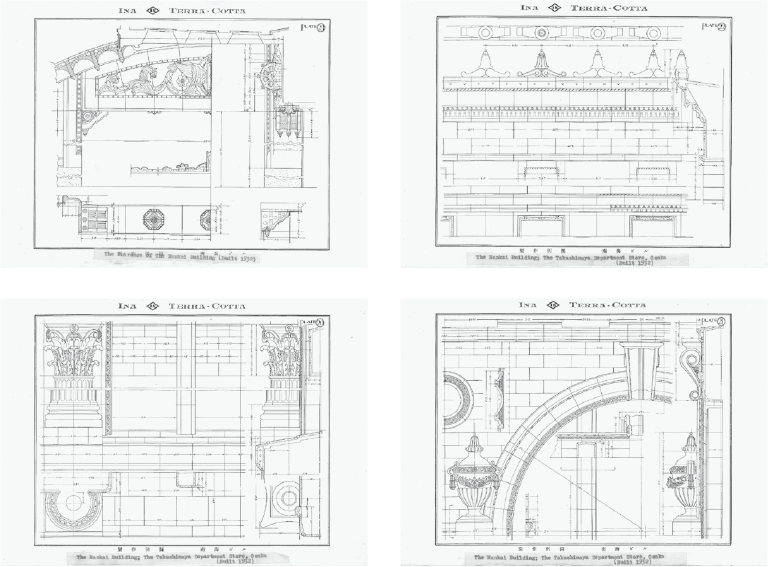

The walls of the Imperial Hotel were adorned with rare yellow scratch face bricks, produced at the Imperial Hotel's brick manufacturing factory in Tokoname. Hatsunojo Ina and his son Chozaburo were invited as technical advisors and, following trial and error by skilled craftsmen, four million bricks and tens of thousands of intricate terracotta pieces were produced, perfectly shaped to meet Wright's specific requirements. Following the completion of the hotel, Ina took on the equipment and the workers of this factory, creating the foundation of Ina Seito (INAX).

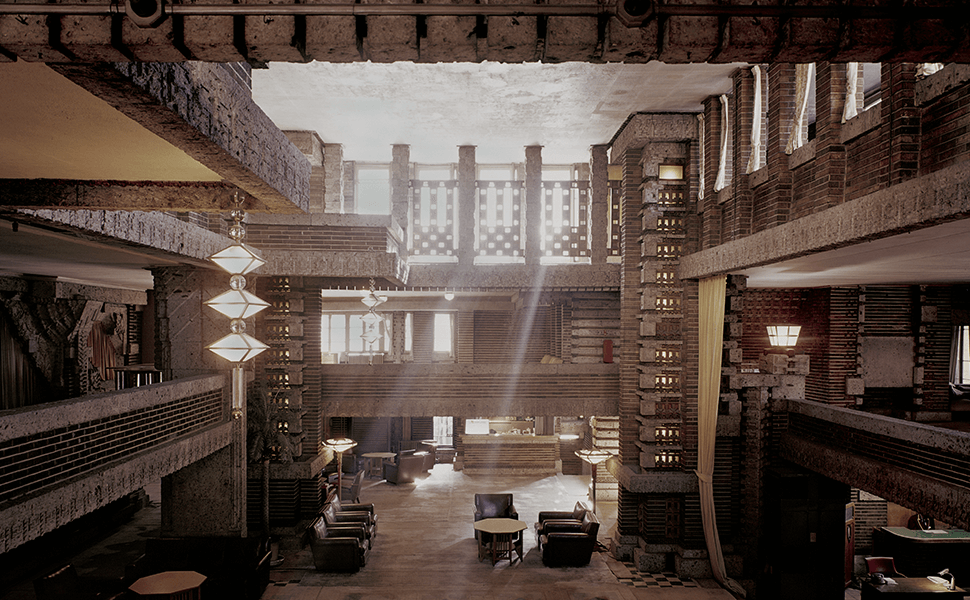

Inside the hotel, ornamental perforations enriched the light and shadow of the interior as sunlight filtered in from the skylights and windows. Wright's calculated use of light combined with scratch faced bricks, carved Oya stones, and intricately designed terracotta produced attractive silhouettes, creating a unique and majestic aesthetic experience.

Wright's Imperial Hotel

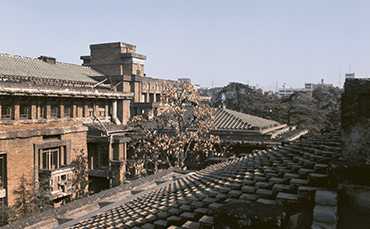

The Imperial Hotel was initially built in 1890 to provide comfortable accommodation to guests from abroad. As Japan modernized, the number of foreign visitors grew rapidly in the early 1900s. To increase capacity, the hotel commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the second building in 1916.

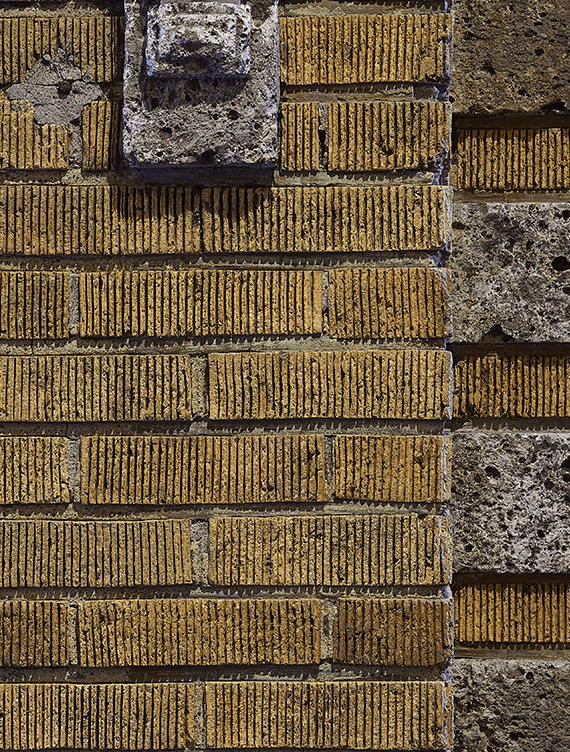

Wright used a revolutionary architectural design that signified Japan's modernity and the cultural interaction between the East and the West. Unlike other typical Western-style red-brick buildings of the time, Wright used yellow scratch face bricks, ornamental terracotta and carved Oya lava stones, resulting in warm earth tones that matched Japanese sensibilities.

The Imperial Hotel became one of the symbolic architectures of modern Japan. Copying the style, scratch face tiles became a popular exterior material, starting the industrial development of exterior building materials suitable for buildings in Japan.

The walls of the Imperial Hotel were adorned with rare yellow scratch face bricks, produced at the Imperial Hotel's brick manufacturing factory in Tokoname. Hatsunojo Ina and his son Chozaburo were invited as technical advisors and, following trial and error by skilled craftsmen, four million bricks and tens of thousands of intricate terracotta pieces were produced, perfectly shaped to meet Wright's specific requirements. Following the completion of the hotel, Ina took on the equipment and the workers of this factory, creating the foundation of Ina Seito (INAX).

Inside the hotel, ornamental perforations enriched the light and shadow of the interior as sunlight filtered in from the skylights and windows. Wright's calculated use of light combined with scratch faced bricks, carved Oya stones, and intricately designed terracotta produced attractive silhouettes, creating a unique and majestic aesthetic experience.

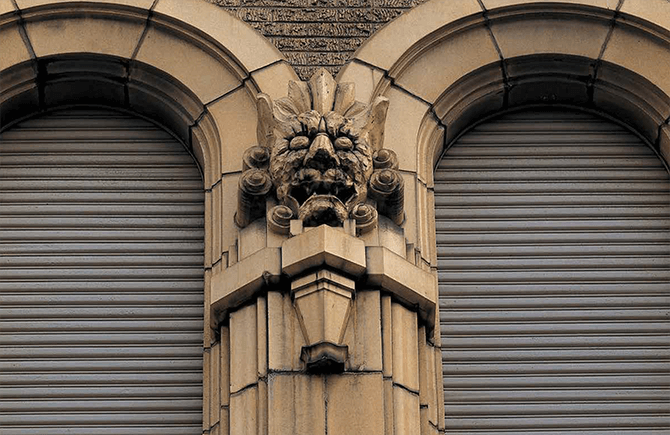

Terracotta Decorations

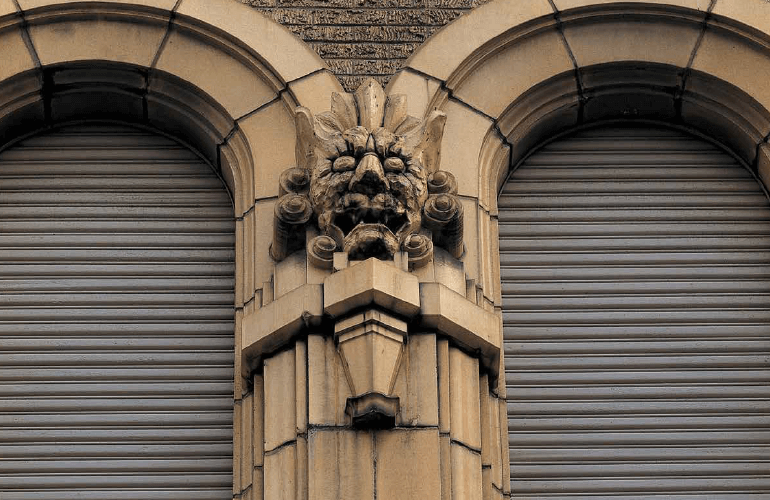

Following the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, new large buildings such as department stores, banks, and government agencies were rebuilt with reinforced concrete and covered with ceramics. These buildings, embellished with flamboyant decorative terracotta, symbolized the recovery of Tokyo.

The trend of decorative buildings quickly spread to other major cities. Decor from various parts of the world was adopted in the designs of ornamental terracotta, and Japanese customs such as symbols of the owner were often also included in the designs.

Equipped with the knowledge gained producing terracotta pieces for the Imperial Hotel, Ina Seito (INAX) became one of the leading terracotta manufacturers in Japan.

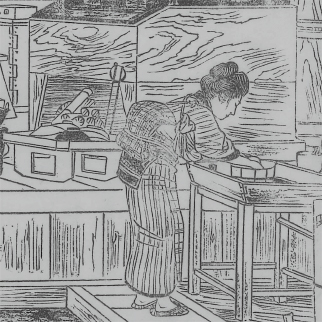

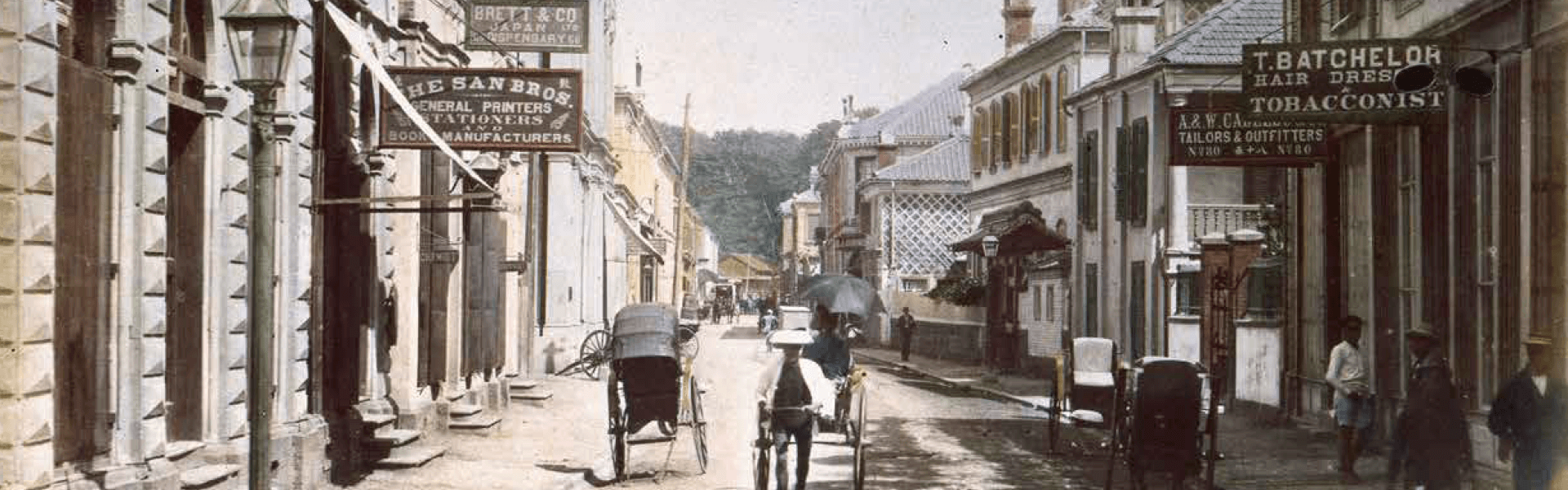

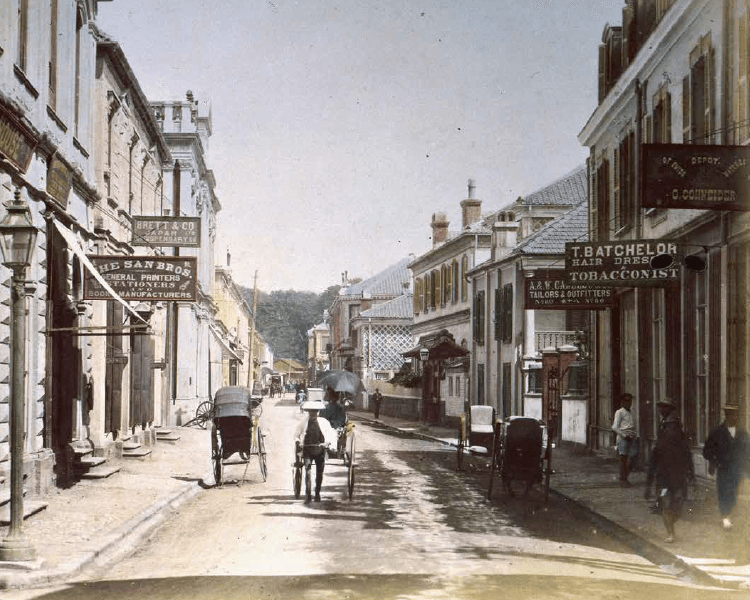

A picture of a foreign settlement in the Meiji period. (Courtesy of Yokohama Archives of History)

Following Commodore Perry's visit, the Edo government signed treaties with five countries in 1858. Citizens of the treaty nations were henceforth permitted to live and work in foreign settlements,

designated areas near the ports specified under the treaties, with extraterritoriality. Foreign settlements were the initial gateway to Japan's westernization and continued until 1899, after which Japan reclaimed their jurisdiction and foreigners were permitted to live anywhere in Japan.

Terracotta Decorations

Following the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, new large buildings such as department stores, banks, and government agencies were rebuilt with reinforced concrete and covered with ceramics. These buildings, embellished with flamboyant decorative terracotta, symbolized the recovery of Tokyo.

The trend of decorative buildings quickly spread to other major cities. Decor from various parts of the world was adopted in the designs of ornamental terracotta, and Japanese customs such as symbols of the owner were often also included in the designs.

Equipped with the knowledge gained producing terracotta pieces for the Imperial Hotel, Ina Seito (INAX) became one of the leading terracotta manufacturers in Japan.

Following Commodore Perry's visit, the Edo government signed treaties with five countries in 1858. Citizens of the treaty nations were henceforth permitted to live and work in foreign settlements,

designated areas near the ports specified under the treaties, with extraterritoriality. Foreign settlements were the initial gateway to Japan's westernization and continued until 1899, after which Japan reclaimed their jurisdiction and foreigners were permitted to live anywhere in Japan.

Earthenware Pipes Key to Japan's Modernization

Earthenware pipes played a less visible yet important role in Japan's modernization. Initially they were introduced to build storm drainage in the Yokohama and Kobe foreign settlements during the Meiji era. Demand for earthenware pipes surged with the urbanization of modern Japan, as they helped to build critical infrastructure for urban living such as water and sewage systems. In the farmland, earthenware pipes were used to develop well-drained paddy fields in damp grounds, which supported the growth of rice farming in Japan.

Before becoming involved in the production of bricks and terracotta for the Imperial Hotel, Hatsunojo Ina started an earthenware pipe manufacturing business in 1902 and operated a mass-production factory in Tokoname.

While pipes were produced in various parts of Japan, those produced in Tokoname and by Ina Seito (INAX) were known for their high quality and used in major cities such as Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe.

The great kiln with a 21m-tall chimney built in 1921 still stands today at the INAX MUSEUMS in Tokoname. The kiln was coal-fired from 14 furnace openings placed evenly on both sides. Due to its extensive size, it took three to four days to fire and 10 days to cool down the kiln. Large pipes with a diameter of 90cm along with other products such as clinker tiles were produced in this kiln during its 50 years of operation. The kiln and the chimney are designated as registered tangible cultural properties of Japan.

Story1 Herovisual: © Toshihide Kajihara

Earthenware Pipes Key to Japan's Modernization

Earthenware pipes played a less visible yet important role in Japan's modernization. Initially they were introduced to build storm drainage in the Yokohama and Kobe foreign settlements during the Meiji era. Demand for earthenware pipes surged with the urbanization of modern Japan, as they helped to build critical infrastructure for urban living such as water and sewage systems. In the farmland, earthenware pipes were used to develop well-drained paddy fields in damp grounds, which supported the growth of rice farming in Japan.

Before becoming involved in the production of bricks and terracotta for the Imperial Hotel, Hatsunojo Ina started an earthenware pipe manufacturing business in 1902 and operated a mass-production factory in Tokoname.

While pipes were produced in various parts of Japan, those produced in Tokoname and by Ina Seito (INAX) were known for their high quality and used in major cities such as Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe.

The great kiln with a 21m-tall chimney built in 1921 still stands today at the INAX MUSEUMS in Tokoname. The kiln was coal-fired from 14 furnace openings placed evenly on both sides. Due to its extensive size, it took three to four days to fire and 10 days to cool down the kiln. Large pipes with a diameter of 90cm along with other products such as clinker tiles were produced in this kiln during its 50 years of operation. The kiln and the chimney are designated as registered tangible cultural properties of Japan.

Story1 Herovisual: © Toshihide Kajihara